The following is a transcript of the opening remarks given at the Science for Social Good satellite event at the Cognitive Computational Neuroscience conference organized by Anne Urai, Ili Ma and myself in Amsterdam on August 11, 2025. Check out Georgia Turner’s blog post about the event posted on Anne Urai’s website.

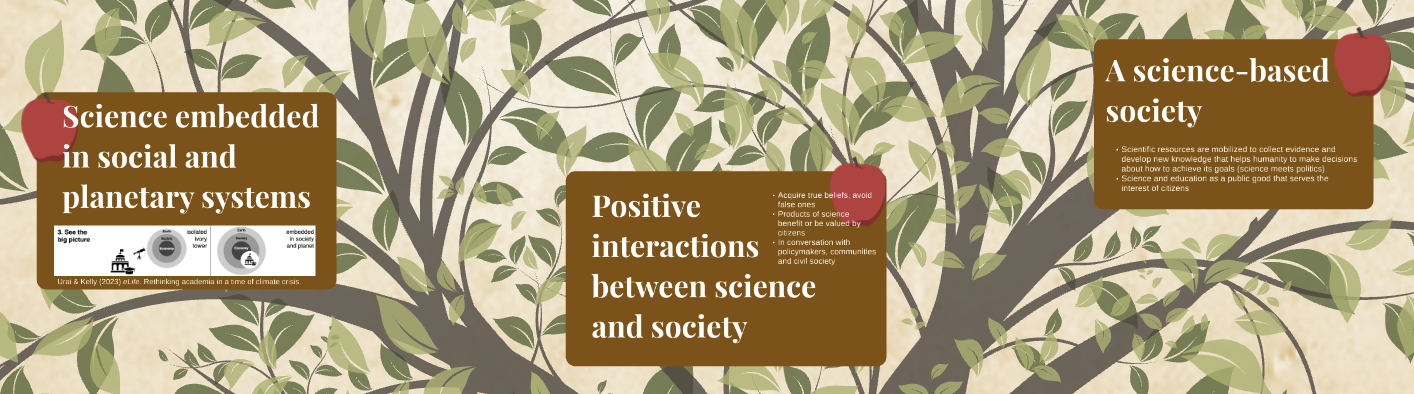

I want to start us off this afternoon by providing an overview of what one could mean when they say ‘science for social good’. I’m going to use this tree as an analogy. Up top are the fruits I want to grow. This is my positive vision of a science for social good. Then in the trunk are the prerequisites—the parts that need to be in place before the fruits can grow. And in the soil are slightly more specific nutrients that we can add to our scientific system to help the tree to grow.

Starting with the fruits

A science for social good abandons the outdated notion of scientific institutions as isolated, ivory towers and instead recognizes that science is always embedded within our social, political, economic, and planetary systems. These systems, particularly systems of power, shape what science gets done and science in turn will reinforce or challenge particular worldviews and have material consequences on our planet’s life support systems.

So these interactions are always happening. A science for social good is trying to amplify the positive interactions while dampening the harmful ones. We want to acquire true beliefs while avoiding false ones, and we want the products of our science to benefit or be valued by citizens. But we recognize that this is a two way street. It needs to be done in conversation with policymakers, communities, and civil society groups who have much to contribute to science itself.

I want to live in a science-based society in which scientific resources are mobilized to collect evidence and develop new knowledge that helps humanity to make decisions about how to best pursue its goals. I want to contribute to science and education as a public good that serves the interests of citizens. This is one place where science meets politics. How do we decide what humanity’s goals and values are if not through politics? through democracy?

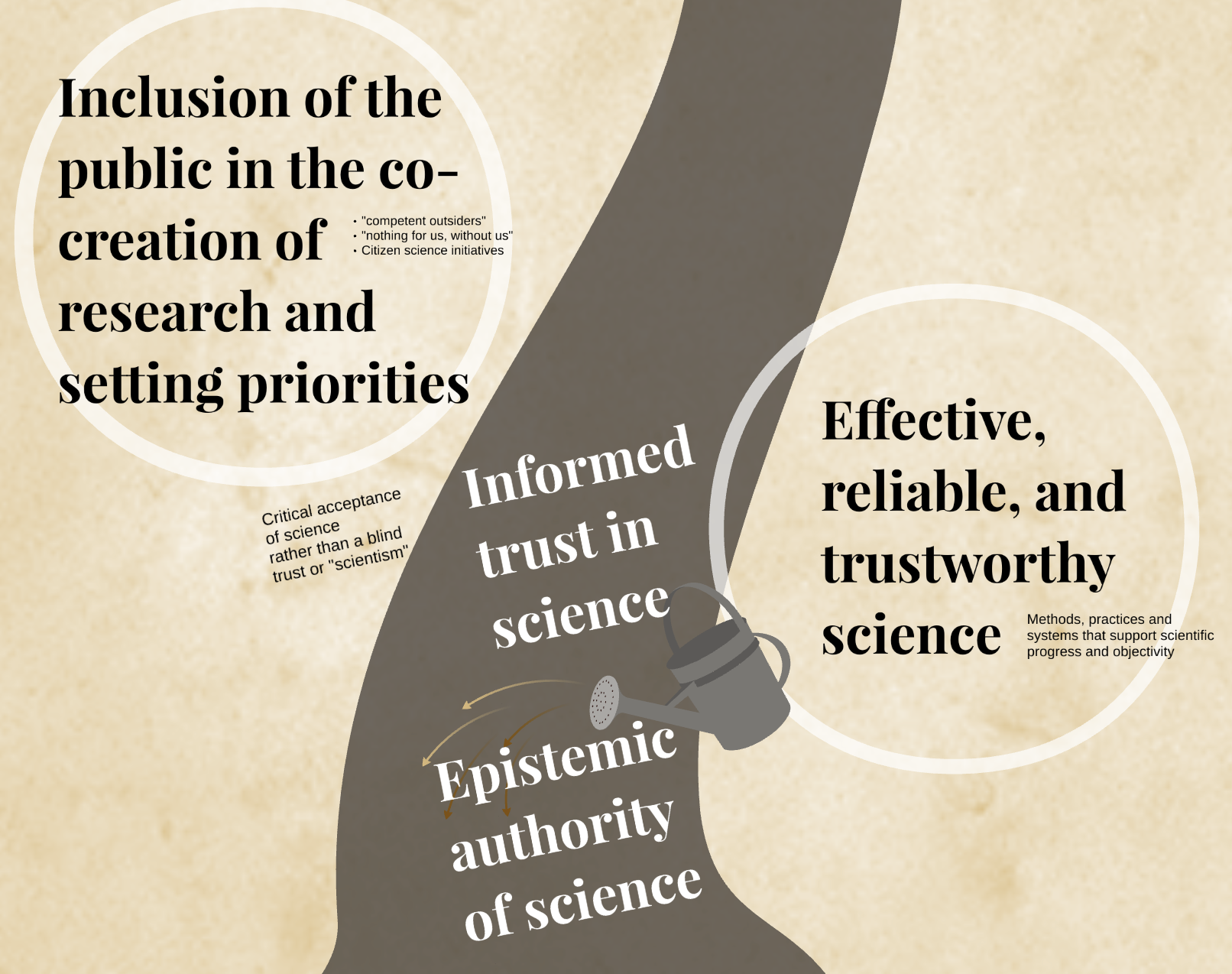

In order for that to become a reality, we’ll need these things in the trunk.

We need the inclusion of the public in the co-creation of research and setting priorities. Co-creation is a hot topic these days, particularly in certain sub-fields. You’ll probably be familiar with it if you work with any special subpopulations where you might have heard the saying ‘nothing for us, without us’. But there is room for all of us to reflect critically on how we orient towards our human participants, the labellers of our machine learning datasets, and the people affected by the technology with create, use, and study.

We need our science to be effective, reliable, and trustworthy. That means we need to nurture and protect the practices and systems that support scientific progress and objectivity.

Then, hopefully decision makers and the public alike can develop an informed trust in science and grant epistemic authority to science. By ‘informed trust’ I mean a critical acceptance of science which recognizes its limitations rather than a blind faith or scientism.

Now I’ll move on to this incomplete list of ingredients or nutrients. I’m sure that you can think of many more to add here.

To achieve an effective, reliable, and trustworthy science we need our science to be open and transparent. Allow me to highlight UNESCO’s Recommendations for Open Science which provides an international framework for open science policy and practice.

We also need critical discourse. We need to be encouraged to challenge each other and we need our scientific community to be sensitive to that criticism. We need diverse values and approaches so that we can best scrutinize each other’s assumptions. We need to reflect on whose interests are reflected in our science. Groups whose interests are not reflected in mainstream science will be justifiably distrustful of that science, and so we must take action to broaden participation in science. For more about the deep sociality of science, check out this easy to read article I wrote for Science for the People Magazine.

Science communication and science education will help to build that informed trust in science I mentioned earlier. A scientifically literate public will then be better able to participate in a science-based society. On this point, I want to emphasize that this is something we can easily get wrong. Not all science education and science communication is helpful on this front.

In preparing this talk, I was quite influenced by this article Sealing the gateways to post-truthism: Restablishing the epistemic authority of science which concludes that ‘educational measures should highlight the social and conversational nature of scientific knowledge production because these concepts lay the foundation for learners’ and citizens’ abilities to build an informed trust in science, and in turn, actively engage in a science-based society.’ See also the book Why Trust Science? by Naomi Oreskes.

Lastly, we need the political will, both to conduct this kind of science and to act on its results. This is another place where science meets politics. If we want a science-based society, we’ll need to advocate for it and engage in activism to bring it about. Personally, I pursue this through my trade union where we are currently building a campaign for education as a public good.

So I hope in this tree you’ll see that it’s not just what we research but how we research that makes a science for social good. There is a buffet of entry points and ways to contribute, regardless of your particular interests.

I deliberately made this a positive vision, but we can equally imagine a mirror image of this tree that summarizes the forces against a science for social good. Science is under attack right now in many parts of the world. Instead of campaigning for a return to the status quo, let us use this moment to remake our scientific systems and repair our relationship with the human and more than human world.

We are the gardeners of our scientific ecosystem. What will we grow?