Michael Silberstein (2002) Reduction, Emergence and Explanation, in The Blackwell Guide to the Philosophy of Science

Two types of reduction:

- Ontological reduction: everything in the world can be reduced to or determined by some irreducible fundamental constituents. Has to do with real world items: entities, events, properties, etc. which can be linked via elimination, idenitity, mereological supervenience (part-whole relations), nomological supervenience/determination.

- Epistemological reduction: scientific theories and laws about the world at a macroscopic level can be reduced to or identified with more fundamental theories and laws. Has to do with representational items: theories, concepts, models, frameworks, schemas, regularities, etc. which can be reduced via replacement, theoretical-derivation, semantic/model-theoretic/structuralist analysis, or via pragmatic approaches. For example, the attempt to reduce thermodynamics to statistical mechanics or the attempt to reduce chemistry to quantum mechanics as failed or incomplete cases of intertheoretic reduction.

Reductionism: belief that both ontological and epistemological reduction is true. Phenomena at one level can be explained by the activities and relations among component parts at a lower level. The goal of science is to map all phenomena onto the ‘real’ fundamental ontology of the world, governed by the most fundamental theories. It is through this process that scientist unify natural phenomena by understanding how diverse sets of activities are governed by the same small number of fundamental theories.

Both types are related: “We would like to believe that the unity of the world will be described in our scientific theories and, in turn, the success of those theories will provide evidence for the ultimate unity and simplicity of the world; things are rarely so straightforward.” (Silberstein p. 81)

Emergentism: Rejection of both types of reductionism. There is no fundamental ontology. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Phenomenological theories cannot be reduced to or identified with more fundamental ones. The “best understanding of complex systems must be sought at the level of the structure, behavior and laws of the whole system and that science may require a plurality of theories (different theories for different domains) to acquire the greatest predictive/explanatory power and the deepest understanding.” (Silberstein p. 81)

Emergentism popular today: “emergent property”, “emergent phenomenon”, lots of examples of observations that are not well explained by reduction to properties and activities of component parts.

This perhaps over-simplified account assigns science’s goal to unify in the reductionist camp and the commitment to explanatory and theoretical plurality with the emergentist camp. But it seems to me that these two aspects need not be completely at odds with each other.

“Emergentism and reductionism might form a continuum and not a dichotomy” (p. 99) e.g. causal mechanical perspective rejects microreduction, says instead that explanatory mechanisms are multi-level, “emphasizing the gradual, partial and fragmentary nature of many real world cases.””

Context-specific strategies for reduction, rather than universal. Good reason to believe “unification of scientific theories will be local as best”— a nested hierarchy of theories rather than a pyramid.

Although some would still say that it is just our ignorance that prevents us from unification. (I’m not convinced)

Miłkowski, M., & Hohol, M. (2020). Explanations in cognitive science: Unification versus pluralism. Synthese.

Special issue in Synthese on Explanations in cognitive science: unification versus pluralism. “Does cognitive science need a grand unifying theory? Should explanatory pluralism be embraced instead? Or maybe local integrative efforts are needed? What are the advantages of explanatory unification as compared to the benefits of explanatory pluralism?”

Original motivation for the interdisciplinary field of cognitive science: multiple research perspectives would be required to explain cognitive phenomena. Founders of cogsci were largely pluralistic in their views on explanation, but advocated for a unified research discipline, i.e. a single object of study but pluralistic methodology.

Two, non-exhaustive types of unification:

- Reductive unity: that all sciences should be reduced to one grand unifying theory, gained some popularity in the 60s. (Carnap 1928, Oppenheim and Putnam 1958). (Can safely reject this at this point)

- Integrative coordination: Scientists from multiple fields should coordinate, gathering evidence from multiple sources but ultimately building integrated models (Neurath 1937, Potochnik 2011) (I’m still on board with this one)

Problems for the received view of reduction in cognitive science:

- Multiple realizability: “the kinds in the theory to be reduced cannot be neatly identified with (collections of) the kinds in the reducing theory, in which there are usually multiple possible kinds that could realize the kinds of the theory to be reduced”

- received view requires theories to take the form of propositional logic and law like statements (and typically assumes a variant of the deductive nomological theory of explanation which states that explanations are deductive arguments). Law like statements, generally defined as exceptionless regularities, are rarely found in cognitive science. Instead, theories in cogsci “are sometimes stated in terms of formal specifications in artificial languages, not all of which are declarative; some are stated in a mixture of diagrams and verbal descriptions, and some as software” (Cooper and Guest 2014) so we cannot derive one theory from another (as the received view of reductionism would have us do)

Integrative coordination

Coordinated or integrated fields, theories, or explanations are not fully autonomous, e.g. psychological theories are constrained by biological facts. Example: Cognitive neuroscience as the integration of cognitive psychology and neuroscience, searching for the neural mechanisms underlying cognitive phenomena.

Carl Craver’s ‘Mosaic Unity of Neuroscience’ view

Craver proposes that good explanations in neuroscience describe constitutive mechanisms, span multiple levels and integrate multiple fields. “mechanistic explanations force piecemeal integration” because

- describing constitutive mechanisms involves identification of the component parts, and how their organization and activities realize the phenomenon to be explained

- various types of evidence may be brought to bear on complex explanations of the phenomena that are realized by neural mechanisms “The mechanistic account of integration is compatible with non-extreme versions of explanatory pluralism.”

Explanatory pluralism is default in cog sci, and this can go hand in hand with integrative efforts or not (as in isolationist pluralism and eliminativist pluralism)

Unifying cognitive science

Alan Newell: “without unification, cognitive science will cease to be cumulative” In 1973, he wrote the article “You can’t play 20 questions with Nature and Win” in which he questioned where current trends in experimental psychology would lead. He finds a large chasm between the general concerns of high level theories and the day-to-day decisions of psychological experiments which occur at lower levels. He makes the observation that much of what the field of experimental psychology accomplishes is description of increasingly long lists of psychological capacities and phenomena—cataloguing psychological effects—without much attempt to unify these phenomena or to build theories that would encompass them. He sees this as a crisis, that, if left unchecked, would leave the field to stagnate. Later (1990), he published Unified Theories of Cognition, where grand unifying theories were supposed to be the cure for the crisis of non-progress he observed in psychology, but without an appeal to reduction. This is perhaps a third sense of unification that is more about understanding and explanation rather than reduction or integration. The alternative strategies proposed in cogsci might take the form of:

- building a theory of entities that are responsible for all observed phenomena (defended in mainstream cogsci, e.g. unified theories of cognition that are theories about mechanisms or representations underlying all of cognition),

- Difficult to build and also to test.

- or study general principles that govern them, appeal to grand principles:

- e.g. predictive coding, negative feedback, classical cognitivism (compuationalism)

- Need not cover all cognitive phenomena

- problems:

- does not suffice to explain individual phenomena, does not offer local misunderstanding

Unification and pluralism in practice

“For defenders of grand principles, simplicity and the universal scope of a theory may be more important than its evidential support. Integration seems more related to evidential support and consistency instead. The defenders of the new mechanistic approach to explanation, for example, usually treat generality as an optional feature of scientific explanation (Craver 2008). Thus, a defender of integration may proceed in a different fashion than a defender of unificatory strategies.” (p. 9)

Unification, defined by dimensions like simplicity, generality and scope, and systematicity, still constitutes a notable virtue of research traditions, even if attempts for grand unifying theories fail to encompass all cognition.

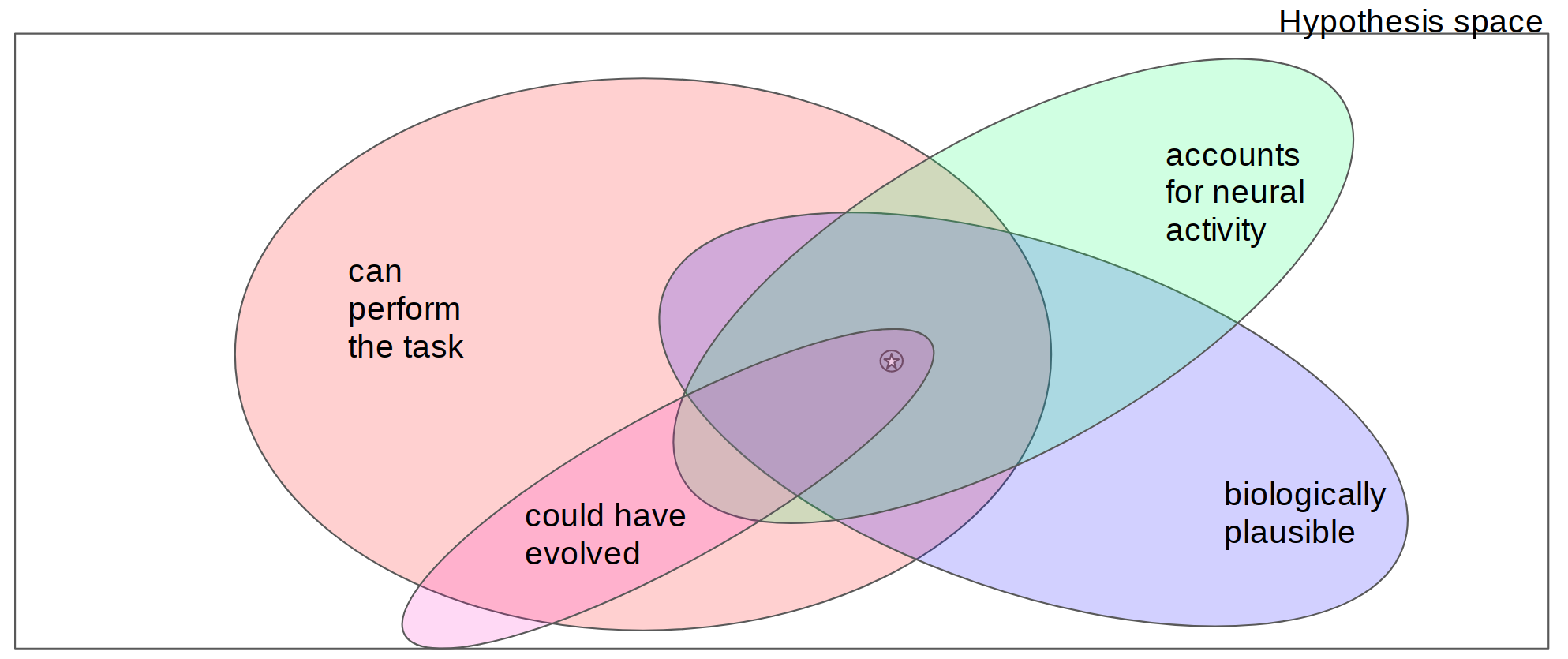

Figure 1. Models lie at the intersection of one or more constraints. The rectangle indicates the space of all possible models where each point in the space represents a different model of some phenomenon. Regions within the coloured ovals correspond to models that satisfy specific specific model constraints (where satisfaction could be defined as passing some threshold of a continuous value). If a constraint is well-justified, this implies that the true model is contained within the set of models that satisfy that constraint. Models that meet more constraints, then, are more likely to live within a smaller region of the hypothesis space and hence will be closer to the truth, indicated by the star in this diagram.

Figure 1. Models lie at the intersection of one or more constraints. The rectangle indicates the space of all possible models where each point in the space represents a different model of some phenomenon. Regions within the coloured ovals correspond to models that satisfy specific specific model constraints (where satisfaction could be defined as passing some threshold of a continuous value). If a constraint is well-justified, this implies that the true model is contained within the set of models that satisfy that constraint. Models that meet more constraints, then, are more likely to live within a smaller region of the hypothesis space and hence will be closer to the truth, indicated by the star in this diagram.